le fa’amoemoe ‘o le’ā to’esea vave atu ai lana tama na fānau ‘a e le’i o’o ‘i ona aso tatau. Peita’i, sā ‘ese ai le fuafuaga a atua.

Sā lātou mua’i fa’atonuina ni galu latou te ‘aveina. atu ‘o ia ‘i le apitāgalu, ona ‘auina atu fo’i lea o se toea’ina na te tausia lelei. Sā fa’apea ai ‘ona i’u ‘ina tupu a’e ma ‘avea ma se tama talavou ‘aulelei.’0 le tasi aso, sā lā feiloa’i ai ma se tama’ita’i. Ma, ‘o le taimi lava na va’aia ai e le tama lea fafine, na ia iloa ai ‘o lona tinā lava lea. Sā ia tu’uina atu lea manatu ‘i a te ia; peita’i, sā le’i talitonu le tama’ita’i, vagana ‘ona ‘ua māe’a lelei ona tala- talaina atu e le tama le tala ‘i lona olaga. Na ‘amata ai loa ona talitonu ma alofa tele atu le tama’ita’i ‘i lana tama; sā ia si’i a’e ma fa’ati’eti’e i ona tau’au i aso ta’itasi. ‘0 lea lā uiga na maua mai ai e Maui lona igoa ‘ua ta’uta’ua i Sāmoa, ‘o Ti’eti’e i Talaga, ‘o lona uiga, “‘O le ti’eti’e i tau’au o Talaga, lona tina.”Sā tuputupu a’e le tama ‘o Maui Ti’eti’e i Talaga ma ‘avea ai ma tagata matua ma le malosi fa’apea ma lona poto masani.

‘0 lona tamā, Ma’eatutala, sa pulea le ma’umaga (fa’ato’aga talo) tele a Māfui’e, ‘o se tagata lāpo’a tele na noro i Pulotu. ‘0 aso ta’itasi i le taeao pō lava, sā alu atu ai le tamā o Maui. ma toe fo’i mai i le afiafi pō. ‘E leai se tasi o le ‘āiga e foliga na te iloa le mea e malaga āga’i ‘i ai le toea’ina. ‘0 le māfua’aga lea na tonu ai le manatu o Maui ’o le’ā na su’eina po ‘o fea e alu atu ‘i ai lona tama, ma po ‘o ni ā fo’i ana gāoioiga o lo ‘o fai ai.

‘0 le mea lea, i le tasi aso, sā ia mulimuli fa’alilolilo atu ai ‘i lona tamā. ‘Ina ‘ua mavae se itūlā e tasi o la lā sāvaliga,

sā ia va’ai atu ‘i lona tamā ’ua tūsasa’o i luma tonu lava o se mauga mato tele, ona ia fa’alogo atu lea ‘o memumemu lona tamā i ni ‘upu uiga ’ese, pei e fa’ataulāitu, ma fa’auta! na māvae ma matala mai le ’ele’ele, ona savali atu ai loa lea o lona tamā ‘i totonu. Sā le fefe ‘o ia i se mea e tasi; ‘o lea, sa ia mulimuli atu ai fo’i ’i lona tamā.

Ina ‘ua iloa mulimuli ane e le tamā lona atali’i, sā ia taumafai loa ‘i ā te ia e toe fo’i. “‘Afai ’e te le toe fo’i,” ‘o lana tala lea ’i lona atali’i, “‘O lo’u matai, le tagata lapo’a tele ‘o Mafui’e, ‘e le taumate ‘o le’ā ia fasioti ‘i ā te ‘oe.

Sa le’i suia ai le loto o Maui, sā le iloa lava e ia se fefe. ‘0 le mea lea, sā ia nofo ai pea lava e ui ‘ina le malie lona tamā. Sa tonu i lona mafaufau ‘o le’a sā’ili mea ‘uma e uiga i lenei nofoaga lilo.

’A ‘o fealualua’i le tama, na taia lana sosogi i se nanamu e uiga ‘ese le manogi. Sā āga’i atu ai loa ‘i le itū lea e sau ai le nanamu, ma na fa’afuase’i ona taunu’u ‘i totonu o le umukuka o Māfui’e, ma na ia maua atu ’i ai se manufata (pua’a) fa’ato’ā māe’a ona fa’avela lelei, fa’apea ma le anoano o talo vela. Sa ia tofo- tofoina loa nā meataumafa. ‘0 ni mea’ai e uiga ‘ese le mānaia, ‘o lona manatu. ifo lea i lona loto, ‘ai se ā e le fa’apea ai ona sāunia a matou talo ma ‘a’ano o manufasi.

‘A ‘o si ona tamā, sā popole pea lava mo .lona ola, na mulimuli atu pea ma fa’apea atu, “‘E leai se afi a tātou. Na ‘o Mafui’e lava e fa’avela ana mea’ai. ‘A e peita’i, la’u pele Māui, ‘ia ‘e toe fo’i nei ‘a e le’i taunu’u mai Māfui’e ma fasioti ‘i ā te ‘oe.” “Se’i maua mai muamua sa’u afi, ona ‘ou alu ai lea,” ‘o le tali lea a Maui.

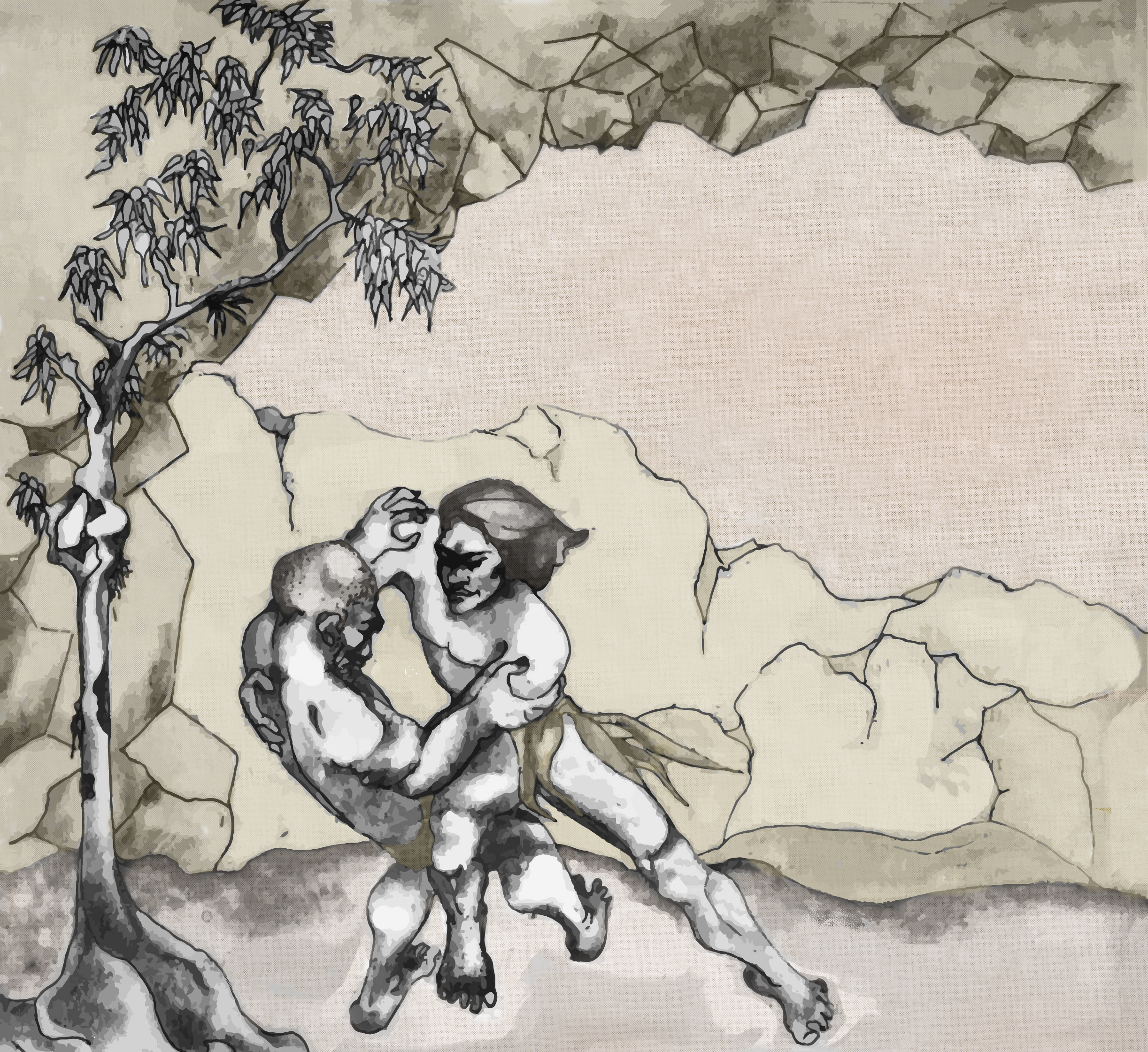

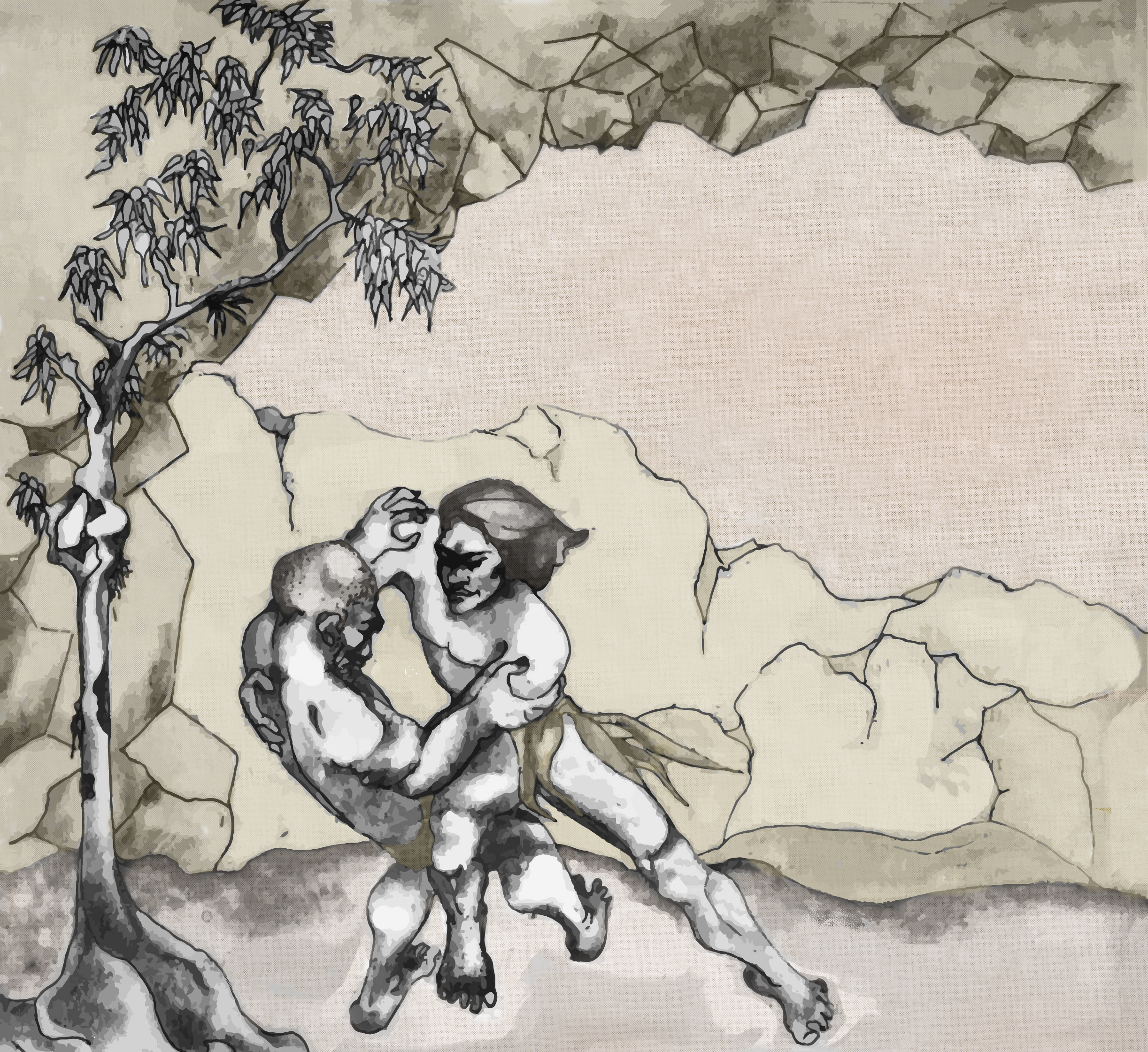

Na fa’afuase’i ona ia oso atu ma tauivi loa ma Maui, Peita’i, na pu’eina e Maui ma fusi ona lima, ona la tauivi ai lava lea pei ni manu-fe’ai mo se taimi ‘umi lava.

Sā le’i fiafa’avaivai se tasi o lā’ua. Na i’u ‘ina maua e Maui le lima o le ali’i tino ‘ese ma mimilo ai lava se’ia o’o ‘ina aue le

ali’i i le tiga. ‘E ui ‘i lea, sa le’i tu’ua ai lava e Maui le lima.Na ia saga mimilo malosi pea se’ia o’o ai ‘ina talosaga atu le ali’i tino ‘ese, ma fa’amolemole ‘ina ‘ia fa’asa’oloto ‘o ia mai ona

māfatiaga. Sā faiatu Maui, ‘e fa’ato’ā mafai ona tatala atu ‘o ia pe ‘ā fai e malie mai lona loto e ‘ave mo ia ni motumotu mai lana

ta’igāafi. Sa malie vave atu ‘i ai le sau’ai. ‘0 le ala lea na maua ai e tagata Sāmoa le ulua’i afi, ma talu mai ai, sā fa’avela meataumafa a tagata Samoa.

Maui, who is known as a god throughout the Pacific, is the son of Maeatutala and Talaga, who are both superhuman deities. This is the story where their son Maui brings fire to the people of Samoa, and therefore the wonderful new delight of the ability to cook food, over the violent resistance of the god of fire Mauife and his gatekeepers, who are mostly understood to be incarnate in the form of birds.

Being his parents’ child, Maui is a demigod who lived in the great expanse of the upper world, long before Samoans had fire. In all stories, Maui is clever, wise and mischievous. His deity mother Talaga was like a tree who floated on the surface of the ocean. His name is also “Ti’eti’e in Talaga” meaning “Rider at Talaga,” named for his riding on his mother’s shoulders in the sea. When he was born, he was born directly into the sea. Sadly, he was promptly abandoned by his mother Talaga, and he was washed ashore. But, instead of leaving him to die on the shore, which his mother intended, his supernatural ancestors came to tend to him, and they raised him as their own, according to Samoan custom.

Once grown into a man, Maui was determined to find his first family; this story tells how he set about to do so, and to find fire for the Samoan people.

Maui searched diligently but when he first found and encountered his mother, Talaga, she resolutely denied him, insisting he was not from her; she told him to go away. Undeterred, (for Maui was fearless and always persevered) he sought to bring her memories alive. He talked to her, entreating her to recall her past, and to remember especially when she had cast him away as a newborn. When she finally did so, her memories sprung to life. She at once recognized him. Over time, her love grew and soon she made him her favorite.

Finally at home, and living with her, Maui came to observe that his mother disappeared daily, and naturally wondered where she went. One day he constructed an elaborate ruse so that he could follow her without her knowledge. In some of the versions of this story, the birds are central to the his discoveries, and in others, in contrast, the birds are essential to narrate the gods’ plan to defeat Maui’s adventures and keep fire for themselves. His father, Maeatutala, was also part of her daily ritual, since only he held the secrets to open the gates to the underworld where all fire was carefully guarded by Mafuie for the use of the gods alone.

Maui set off one morning, surreptitiously, following his mother Talaga. His father accompanied him, and gave him a warning, entreating, “My son, my favorite, if you come upon the Great God Mafuie, he will likely kill you” But while Maui was respectful, he was always fearless. He did not heed his father’s warning, and his father assented to his decision. They proceeded up the steep mountain to the wall of black rock beyond which the underworld was hidden. His father opened the path to the underworld, in the usual way, by shouting strange words, using these words as charms, which some believed were words of witchcraft: Fa’atualaitu!

Entering the underworld, Maui confronted Mafuie, the fire deity, and told him his intentions. Jealous and protective of his powers over fire and its secrets, Mafuie set upon to attack the younger Maui with great violence. But Maui was ready, heeding his father’s warning about Mafuie’s threat, and subdued him in a great struggle.

First, Maui caught one of Mafuie’s arms and broke it off entirely. Since Mafuie was God of Fire, he also controlled the earthquakes and volcanoes. He begged to be released, so he could keep his other arm, and continue to control earthquakes and volcanoes. Although this was for the benefit of all Samoans, Maui saw his advantage, and, with his wiles, agreed to release Mafuie, but only in exchange for the gift of fire. Mafuie’s arms struggled like wild animals for a long time, but finally relented, and he agreed to give Maui fire.

Maui took Mafuie’s secrets of fire from the underworld and gave these to the Samoan people, and afterwards, they were able to delight in the gift of cooked food for the first time.

Another version of the story of how Maui brought fire to Samoa (by wrestling the giant god Mafuie) is much less violent and confrontational. It is important, in balance, because it illuminates the differences between the fire-teacher and the fire-finder. Here the fire teacher is highlighted. Throughout the Pacific, Maui engages in various clever, trickster schemes to convince or seduce the fire goddess (his grandmother), since fire is always stolen, since the gods are always unwilling to relinquish their powers to own and ignite a fire, and thereby keep its wealth to themselves. Maui tricks her out of almost all her powers, by extinguishing all the embers she gives to him and going back for more, thus depleting her supply to almost nothing.

At the last possible moment, she realizes his intentions and terrible betrayal, and throws all of the burning embers remaining to her which he has not stolen or kidnapped into the most suitable trees, especially the Banyan Tree. But only she knows into which trees the embers landed. The forest becomes thereafter an expanse of mysterious lights which are hidden, but illuminate the night. There the embers remain, intermittently sparkling, perhaps like lightning, giving bursts of light to make the night alive. Since only Maui knows these secrets, only he can teach the people of Samoa how to start a fire, but he does not teach everyone. The next story sets forth the rules and understandings he taught about how to make a fire. Notice how in this story the elder grandmother outsmarts her younger and frankly disrespectful grandson, bringing yet another gift of night lights, perhaps fireflies, to the Samoans. to illuminate the night sky.

See especially, Bukova, Martina, “Variations of Myth Concerning the Origin of Fire in Eastern Polynesia,” J. Asian and African Studies, 18, 2009, 2, 324-323.