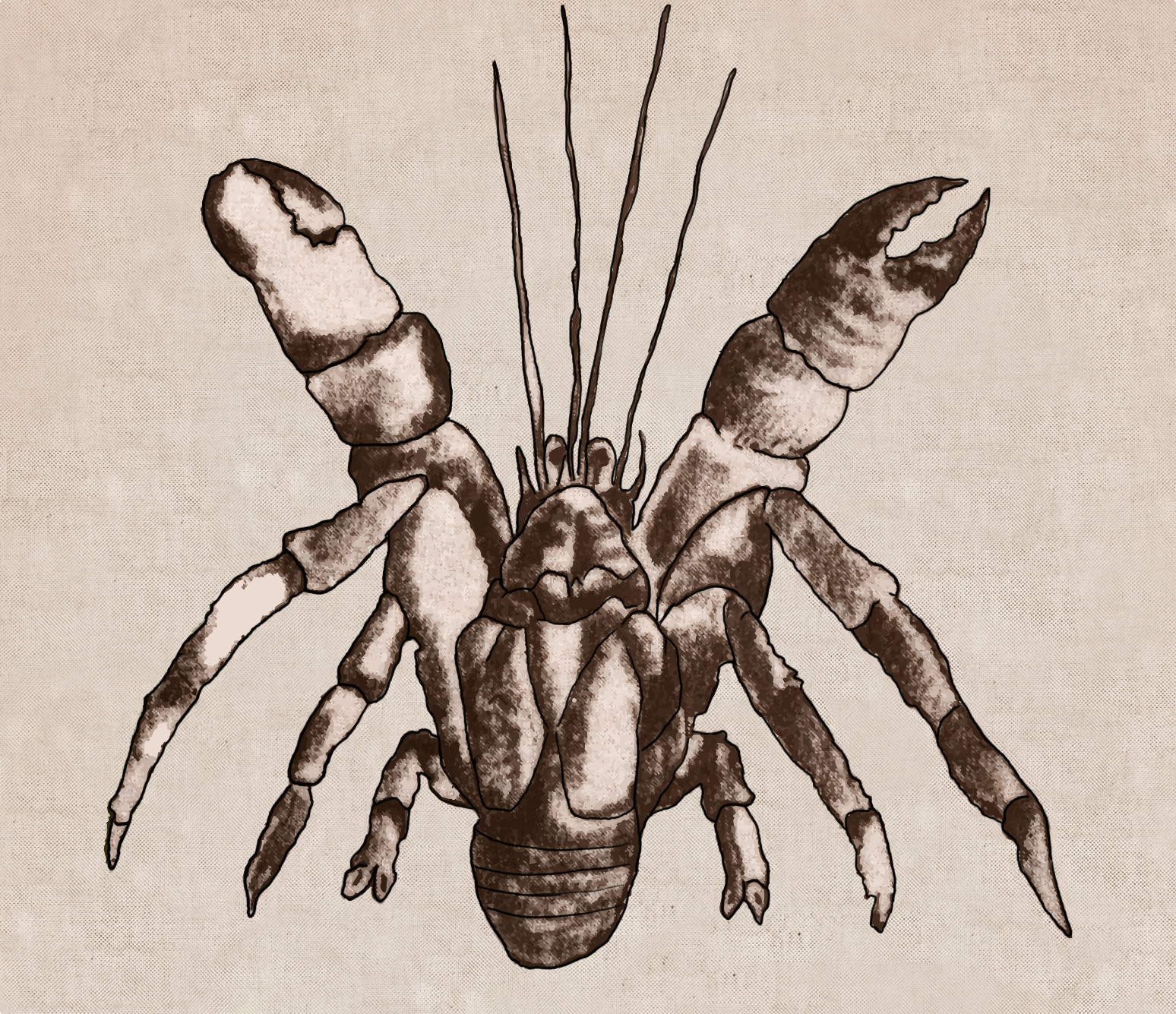

It was earlier noted that our war god takes the shape of the fe’e (octopus) when at sea, the form of a white shell (pule) when he comes on land, and that of a soldier crab (uga) when he lives on a mountain. (Image 98*)

“Finally, the great day dawned. At the call of the conch shell the people gathered on the malae. “

The Feast

While Tamalelagi was sitting with his niece So’oa’emalelagi and his high chiefs in the large meeting house, Nu’ususala, the warriors were feasting dancing and singing. The afternoon passed pleasantly. As evening came and the sun sank below the horizon, laughter and shouting were suddenly interrupted by a strange and unfamiliar song coming from Mount Fao near Fagaloa Bay in Atua. It was the terrible war song of the uga.

The sudden silence, as well as the strange song made a deep impression upon the young chief. As the singing ceased, Tamalelagi said, “In memory of this song and of the uga which sat on a stone in my bathing pool, let us call our malae ‘Ma’auga’. The two best warriors shall be added to our Falefitu, which in the future shall be known as Faleiva (the House of Nine) and henceforth the title of Tuia’ana shall be conferred by these nine orators. Finally, Alipia, my advisor and counselor, shall be the head of the Sausi families who are nearly all related to me”.

Alipia and the two warriors thanked their chief for the tofiga (appointment). Then So’oa’e, who as we have seen, had been invested by Nafanua with the authority and power of a prime minister, said to her cousin Tamalelagi, “As Nafanua is the national war god, so is Fe’e the war god of A’ana. It is true that through her scheming Nafanua holds the four high titles, yet I feel sure that we can get them back if we put our trust in the Fe’e. The song we have just listened to is a sign of his favour, of his willingness to further our interests. I need not remind you that our war god takes the shape of the fe’e (octopus) when at sea, the form of a white shell (pule) when he comes on land, and that of a soldier crab (uga) when he lives on a mountain. So the song we have heard was really that of our protector, the Fe’e. Let Tamalelagi place the welfare of our district in his care and let us hold a yearly feast in the god’s honour, this feast to be called ‘Ole Tapu o A’ana i le Fe’e”.

The proposal was approved by the Assembly and Tamalelagi, who was only too anxious to court the favour of the mighty Fe’e, ordered that on the morrow messengers be sent to invite all Samoa to the first official fea given by A’ana to the Fe’.

The feast was to take place at the first full moon on Ma’auga, the sacred malae of Leulumoega.

As the appointed day approached, people from all parts of Upolu and Savai’i prepaired to Leulumoega. Hecatombs of food were prepared by the hosts; hundreds of pigs had been slaughtered, thousands of taro and breadfruits were prepared for the expected guests.

The day before the feast was a very busy one, not only for the young men who had to do the cooking, but also for Alipia and the orators of the Faleiva. Every visiting village had to be welcomed separately and accommodation had to be provided for them in one of the houses. Probably the only one who attended A’ana worship of the Fe’e with reluctance was Tupa’i, the priest and minister of Nafanua. He had followed closely the recent events in A’ana and felt convinced that the feast would result in a greater unity of A’ana and help to frustrate the hopes of Tonumaipe’a.

Finally, the great day dawned. At the call of the conch shell the people gathered on the malae. Here each village had its appointed place, and when all had sat down the immense gathering looked very much like a circle of chiefs sitting in the guest house.

Alipia had been chosen to make the official speech of welcome. He was dressed in native cloth and wore a beautiful necklace. He leaned on his long orator’s staff and his fly-switch was thrown gracefully over his shoulder.

A formal speech begins with citing the honorific attributes of the place or district and the titles of all the high chiefs and orators. The ceremonial greeting is called Fa’alupega. A mistake, or omission, in the citation of the titles is tantamount to an insult.

Alipia knew this all too well, but as there had never been a gathering representative of all the high chiefs of Upolu and Savai’i, the customary formula would be inadequate.

Alipia, however, knew what would be fitting. Being aware of the political influence of Savai’i, due to the combined offer of Nafanua and Tonumaipe’a, he started with a loud and solemn voice:

WAR AGAINST MALIETOA

“Tulou na a ‘oe, Pule; Tulou na a oulua Tumua; Tulou na a le aiga i le tai; Tulou na a Alataua ma ltu’au.” Greetings to you, Savai’i; Greetings to Atua and A’ana; Greetings to Manono; Greetings to Safata and Faleata.

This resounding greeting over, he made a well-worded speech of welcome to the gathered people and explained the purpose of the new feast.

Alipia’s words were well received and his impromptu welcome has ever since been the official greeting formula for Upolu and Savai’i when meeting together.

Later, after the wars of Fonoti, one more title was added to the above set. It is: “Tulou na a Va’aofonoti,” greetings to Faleapuna and Fagaloa. This distinction was accorded to the two villages because of the assistance their fleet had given in the cause of Fonoti.

Many more speeches were delivered, but when the official ceremonies were over, the sound of the conch shell invited the young men to serve the food. After dinner the games began: wrestling, club matches and spear throwing. A second meal in the evening was followed by the dances. First the young men and girls went through their evolutions. Later elderly men and women mixed with the young people and the dances soon ended in orgies which were beyond all description (poula).

The following day was a day of rest, for rest they needed after such a night. When the feasting had come to an end the visitors returned to their villages.

Comments are closed here.