‘0 isi sivali na ‘auina atu ‘i le Tui Ātua, ma fautuaina ai ‘ina ‘ia nofo sāuni ‘ina ne’i mana’omia lana fesoasoani. ‘0 Sāfata ma Faleata, ‘e ui ina e i le itū o Mālietoa ma lona itūmālō, sa logoina fo’i, ‘a e le’i fa’atagisia se fesoasoani.

‘0 ni aso vevesi ia aso e lua sā tolopōina ‘i ai. ‘0 le tasi vāega o taulele’a sā sāunia ni uatogi; ‘o isi sā lātou vā’aia 1e itū tau i meatau- mafa ‘ia lava mo vaegā’au’ua le ‘o toe mamao ona fa’apotopoto ‘1 Leulumoega.

‘Ina ‘ua malu le afiafi o le aso taupōina, sā gāsolo atu vaegā’au o tau- lele’a ‘1 Leulumoega, ‘ua ‘uma lelei fo’i ona sāuni tau o ‘ilātou. ‘E tele ma tele tagata sā gāsolo atu, se’ia o’o ai lava’ina māofa ‘Alipia i le fa’amaoni tele o tagata ‘i ā Tamaalelagi. Fa’ato’ā ve’aia lea e ia A’ana ua fa atasia, taluai e o’o lava ‘i vaegā’au mai nu’u mamao, e ?ai Faleiatai, sa malaga mai ma sā sāunia ai fo’i e tau mo 1o lātou ali’i talavou.

I le tūlua o po_ma ao na malaga atu Tamaalelagi e asiasi ‘i lana vaegāa l’e to’atele o ‘ilātou; sā ia mimita tele fo’i e ‘au ‘ātoa, ma sā ia vā’aia eaa’oaia’le ‘autau ‘ātoa; ‘o le mua’au ma le itu au (vaega tele). 1.»5:e,°ta’°u;i o\ei ^/a’aeāoni Sā vaevae ‘1 vaega e a e.

‘0 le muā’au, sa aofia a fa’atonuina ‘ilātou e osofa ia Faeitn’nuta. Fasito’otai, ma Sagafili – sā . vaveao> ma ‘ia maua mai ai ni ulu se tele lava. ‘0 le vaega tele, o ie tonuga. fa«ata1l- mo ni 1S1 fa’an. Sa sāunia loa le mua au mo fatauioa. ‘0 ni lefulefu mai ni ‘aulama, tega 0 tama’ita’i mātutua ‘ua fai a lātosā vali ai o lātou mata. Ona o a mumumumuga, ma mili tino o le autau, maise le ‘autalavou ‘i suāu’u.

‘O ni teine muli sS soso’o ai, na lātou teuteuina lelei tino o le ‘autau ‘i ni ‘ula. S3 sāunia loa le ‘autau mo le taua.

Preparation: The oracle’s pronouncement was no sooner made public than Tamalelagi and his Falefitu prepared for war. Messengers (savali) were despatched to all parts of A’ana, bidding the chiefs to assemble in Leulumoega two days after darkness had set in.

Other messengers were sent to the Tuiatua advising him to hold himself in readiness, should his assistance be required. Safata and Faleata, though belonging to Malietoa’s district, were also informed but neither were asked for help.

The two days of delay were very busy ones. Some of the young men had to prepare additional war clubs; others had to see that there was plenty of food for the warriors who would soon congregate in Leulumoega.

At nightfall of the appointed day, troops of young men and seasoned warriors arrived at the capital. More and more came, until even the old Alipia wondered at the loyalty of the people to Tamalelagi. Never before had he seen A’ana so united, for even warriors from distant Falelatai were there, ready to fight for their young chief.

At midnight Tamalelagi went to inspect his army and seeing their extraordinary number, he was proud, indeed, to be the leader of such a loyal people. He proceeded to divide them into two groups: the vanguard (mua’au) and the main army (itu’au).

The vanguard, consisting of the warriors of Fasito’outa, Fasito’otai, and Sagafili, was ordered to attack Saleimoa in the early morning and to take as many heads as possible. The main body of the army would rest and await further orders.

The vanguards made ready for the fray. With the ashes of burnt coconut leaves they blackened their faces. Then the old women came. Muttering unintelligible incantations, they rubbed the warriors, especially the younger ones, all over with oil. Pretty young maids now gave the finishing touches, decorating their lovers with sweet scented necklaces. The warriors were then ready for the battle.

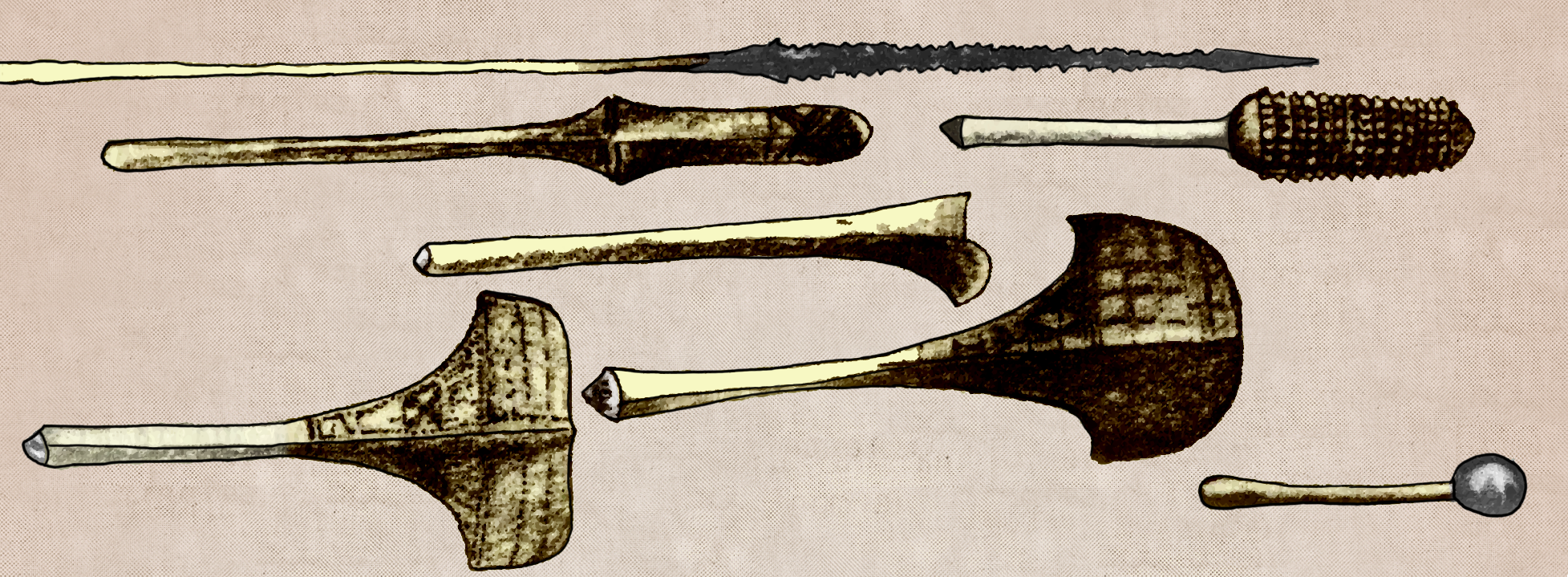

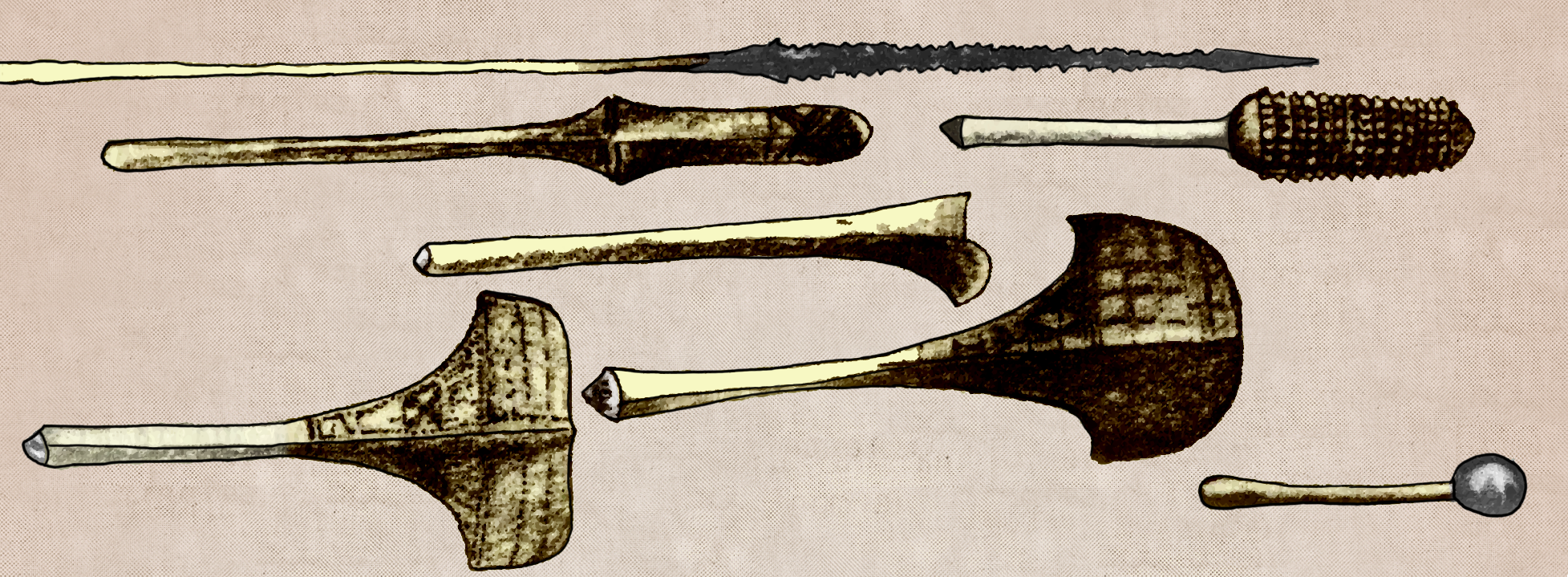

Warfare: The most widely used weapons at that time were clubs. They were short, but heavy and effective in hand to hand fighting. Made in a hurry, they would be discarded after the battle. This club was called ‘Uatogi’ and was usually made of hard toa wood. The old warriors, however, were provided with clubs made for more lasting use. These weapons were often ornamented and highly valued by their owners. Many of them ended in a 12 inch long serrated blade, all of toa wood, as iron at that time was unknown. Those ending in a pointed hook were called ‘nifo’oti‘ (head knife) and served to cut off the head of the vanquished enemy.

As a sign of recognition the warriors wore around their foreheads a strip of tapa cloth (tagavai). The A’ana and Atua people, who in most wars were allies, used to wear a white turban, while Malietoa and his allies wore a red one. Spears were also used, but mostly in single fights. Sometimes such a combat between two heroes (toa), one representing each side, would take the place of a general battle and even decide a war. Stones hurled from slings with extraordinary accuracy would frequently cause broken bones.

A club that had become famous was held in great veneration, and when its owners died, it would either be laid on his grave or be kept by his family as a sacred heirloom. Such a club was called ‘anava’.

Generally, a war was carried on by sea and land. The fleet (fuava’a) was given a free hand. It attacked where and when it promised to bring the greatest success. The army (itutaua) was divided into different groups; the vanguard (mua’au), the main army (itu’au), and those appointed to go through the bush and try to attack the enemy from the flank or rear. The fleet, as well as these bushmen, were especially feared, because none knew of their whereabouts and which village would be the next object of their night attack.

Some of these fleets had their own flag, their particular name, and the sacred symbol of their war god was always taken with them on the warpath. So, for instance, the well known fleet of Manono had the name of Fuatava’a; it carried a wooden drum (lali) called Limuiimuta, and from its mast flew a long white pennant (Samalulu), a symbol of their war god, the Matu’u (heron).

Beginning of Hostilities: In accordance with the orders received from their chief, the vanguard had set out to bring in a few heads. The first village they reached was Tufulele, but secret as the movements of the A’ana troops had been, the news of it had spread and the village had been abandoned. So on they went to Saleimoa, where they still found a few warriors fast asleep in their houses. The ominous war cry ‘Tui’ana!” awoke them. Grasping a club or spear, they defended themselves as well as they could. But the hundred men of the vanguard were too many for them. Soon they were knocked down, their heads cut off, and their houses set on fire.

When the A’ana warriors heard that the troops of Malietoa had concentrated at the next village, they resolved to return, the more so as their objective had been accomplished without the loss of a single man. However, before they left the village they found a number of pigs. These, as well as some fine mats and the six heads they had captured, were taken to Leulumoega and placed before their chief as proof of their success.

Tamalelagi thanked them for their bravery, allotted them all the pigs, and ordered them to rest during the day. The six captured heads would be offered to Fe’e as soon as the war was ended. Calling his chieftains together, Tamalelagi issued his orders for the main army. They were to be executed before Malietoa had time to gather all his troops. The greater part of the army was to proceed by the road. Some picked warriors were to act as bushmen with orders to outflank the enemy and time their attack in such a way as to give the greatest assistance to the main force.

All this was faithfully carried out, and before long the hostile armies faced each other. The fight started with great fury, but it soon became obvious that the odds were very much in favour of Tamalelagi. Malietoa, seeing that his cause was lost, decided to submit to A’ana. His chiefs agreed with him and a messenger was sent to Tamalelagi to ask for peace and clemency, as well as to offer due amends for the insult heaped upon him by the Saleimoa people.

Tamalelagi accepted the offer graciously, for he thought it was to his advantage to have a neighbour as a friend, rather than a brooding enemy. He did not submit Malietoa to the customary humiliation (ifoga) and the only redress he insisted upon was the restoration of Tufulele to A’ana, and that of Saluafata and Solosolo to Atua. All those villages had been annexed to Tuamasaga by the former Malietoa.

Malietoa and his staff willingly accepted the terms; in fact, they found Tamalelagi very conciliatory, for he had even returned the captured heads to the respective families.

Greatly satisfied, Tamalelagi and his warriors returned to Leulumoega to prepare a big feast in honour of their war god the Fe’e, to whom they attributed their victory.

Comments are closed here.